Universities are springing up in China, Korea, India and the Middle East, posing a potential threat to the supremacy of western institutions.It's a pretty arrogant statement. Not only are Western institutions superior, but the 'threat' of other institutions is thinkable, slightly frightening, but still only pose 'a potential threat.'

Just some drivel from a PhD student in 17th century English literature. Masoret is Hebrew for tradition; Masor is also the Hebrew word for saw. Since i hope to be learning and blogging about traditional woodworking (amongst sundry other things), i thought it was an apt play on words. Before you ask, yes, i have a glamorous social life.

Wednesday 29 July 2009

British and American universities 'should merge to beat competition' - Times Online

Thursday 23 July 2009

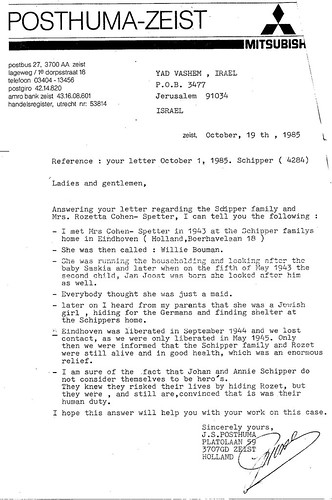

Other Stuff the Schippers Were up to During the War

Wednesday 22 July 2009

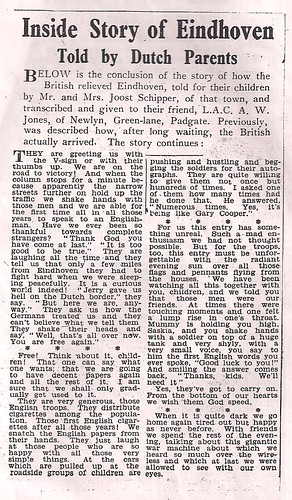

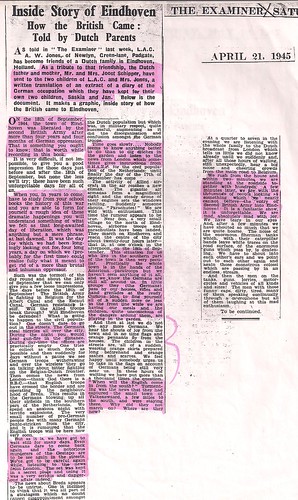

For Joost: The Examiner Articles

Tuesday 21 July 2009

John Ruskin--the Preferred Critic of Woodworkers Since 1819

It is hard to overstate John Ruskin's impact on art, and the more i read about him, the more i am convinced that this post will not do justice to the man who, according to Charlotte Bronte, taught an entire generation how to see. His proteges included John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, Oscar Wilde, and William Morris. His writings on political economy were also not bad. Cecil Rhodes and Tolstoy were fans. Gandhi had something of a conversion experience whilst reading Ruskin's Unto This Last on a train from Johannesburg to Durban. According to a survey of the first Parliament in which Labour managed to get seats, that very book had more of an impact on the Labour Party members than Das Kapital.

It is hard to overstate John Ruskin's impact on art, and the more i read about him, the more i am convinced that this post will not do justice to the man who, according to Charlotte Bronte, taught an entire generation how to see. His proteges included John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, Oscar Wilde, and William Morris. His writings on political economy were also not bad. Cecil Rhodes and Tolstoy were fans. Gandhi had something of a conversion experience whilst reading Ruskin's Unto This Last on a train from Johannesburg to Durban. According to a survey of the first Parliament in which Labour managed to get seats, that very book had more of an impact on the Labour Party members than Das Kapital. The Seven Lamps of Architecture was published in May 1849, the first of Ruskin's works to carry his name, and the first to be illustrated, with fourteen plates drawn and etched by him. A reference in the preface to the depredations of 'the Restorer, or Revolutionist' made Ruskin's position clear. He wished to protect what survived, and draw from it certain principles which would influence the direction of the Gothic revival, notably towards the use of Gothic in secular buildings. His purpose was both to secularize and make protestant the movement, drawing it away from the Roman Catholic influence of Augustus Welby Pugin. His intervention was theoretical rather than practical: the 'lamps' of architecture were moral categories-sacrifice, truth, power, beauty, life, memory, and obedience. Like the types of typical beauty in Modern Painters, volume 2, they are abstract notions in themselves, but for Ruskin were manifested in particular Gothic buildings in Italy and northern France. (ODNB)

Ruskin recruited Wilde into a group of social activists trying to build a road, and his anger at social cruelty found fallow soil in the boy from the famine-writers' house. Pater and Ruskin shaped Wilde's thought and its expression: they did not originate it. Initially he brought their ideas and his glosses into the market place in lectures on aesthetics in the UK and the USA. Thereafter he embedded them, begirt in his own wit and charm, in fictions such as The Happy Prince and other Tales and The Picture of Dorian Gray. (ODNB Wilde entry)Ruskin was also friendly with Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, who shared Ruskin's love of sketching (and definitely exceeded Ruskin's love of little girls) and wished to illustrate his own works, such as The Adventures of Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass. Dodgson had already taken a step back from his work by publishing under the pseudonym 'Lewis Carroll'. Ruskin informed Dodgson that his talents as an artist were 'severely limited.' Dogdson took Ruskin's criticisms quite well, and relinquished even more artistic involvment in his work, hiring professionals to illustrate his books. Nonetheless, Dodgson continued to enjoy sketching and socialised with many artists who were also amongst Ruskin's circle of friends, such as Arthur Hughes, William Holman Hunt, J. E. Millais, Alexander Munro, V. Princep, D. G. Rossetti, J. Sant, C. A. Swinburne, Mrs E. M. Ward, and G. F. Watts.

There is little that is certain about the intimate details of Ruskin's marriage to Euphemia Chalmers Gray beyond the fact that it was never consummated. A medical examination confirmed Effie's virginity, but in a legal deposition that was not introduced in court, Ruskin stated: 'I can prove my virility at once'. This was never put to the test, [thankfully!] but it seems likely that Ruskin was referring to masturbation. Again, there is no confirmation of this, but a letter to a confidante, Mrs Cowper, in 1868 in which he wrote 'Have I not often told you that I was another Rousseau?' has been taken as a discreet reference to the practice. [i don't get it...] At this same time he told a male friend that he had been capable of consummating his marriage, but that he had not loved Effie sufficiently to want to do so. (ODNB)

Tuesday 14 July 2009

John Keble, The Oxford Movement, And Woodworking

Since Keble was the first modern editor of Richard Hooker, this mental image quickly wore off for me (though i kind of still want soft chocolate-chip cookies when i hear his name. Mmm...). In reviewing my chapter on Hooker's Hebraism, I came across a passage in which he was discussing Jewish catechisms. We have catechisms? Last week i was watching a film with my friend and her brother in which the word 'catechism' came up; both blankly looked at me and asked, 'what's that?' Keble identifies this Jewish catechism as Rabbi Abraham ben Hananiah Jaghel of Montfelice's Lekach Tob, and afterwards adding:

Since Keble was the first modern editor of Richard Hooker, this mental image quickly wore off for me (though i kind of still want soft chocolate-chip cookies when i hear his name. Mmm...). In reviewing my chapter on Hooker's Hebraism, I came across a passage in which he was discussing Jewish catechisms. We have catechisms? Last week i was watching a film with my friend and her brother in which the word 'catechism' came up; both blankly looked at me and asked, 'what's that?' Keble identifies this Jewish catechism as Rabbi Abraham ben Hananiah Jaghel of Montfelice's Lekach Tob, and afterwards adding:It is satisfactory to know that the writer became afterwards a Christian.Momentarily morphing into my sister, i thought, Um...rude! And false...What's up with that comment? Hooker was writing before Jews were allowed back into England (the first country to have expelled the Jews in 1290), but Keble was writing well after the Jew Bill; I wonder if that is a factor in allowing himself to say something like that. In other words, i would have expected it from Hooker. That's really a minor aside, yet one that got me thinking. The real question is, what was going on in England during Keble's time that prompted him to edit Hooker and how did this effect his portrayal of Hooker's work? So for the past few days, I have been asking myself, who was this dude? And the answers have been pretty cool. Yes, it connects with woodworking, and no, i didn't have to force it (well, barely).

Some background: With the Reform Act--or the restructuring of English society between 1828-1832, the idea of the Church and Commonwealth being one society was basically chucked out the window. The Oxford Movement was a response to the separation of church and state and an attempt to re-establish the Catholic character of the Church of England. Interestingly, everyone who wrote on this topic, from Coleridge to Peele had recourse to Richard Hooker. But it was probably the Congregationalist historian Benjamin Hanbury's 1830 edition of Hooker's works and his contention that Hooker was 'ably supported by Locke and Hoadly' that Keble was primarily reacting to. Keble specifically denounced Locke, Hoadly, and all their rationalist and liberal followers, from which he decided to liberate Hooker with his edition of Of the Lawes of Ecclesiastical Polity which he published in 1836. Three years before, Keble had gotten the ball rolling.

In linking creed and feeling, Keble witnessed to (and himself furthered) the change in sensibility we associate with Romanticism. By bringing the dangers of Romanticism under the discipline of religious self-control Keble contributed to what one historian has aptly described as 'the Victorian Churching of Romanticism'. It is not surprising, therefore, that Wordsworth, despite his radical past, was Keble's chief influence. Keble had been introduced as an undergraduate to his poetry by Coleridge's nephew, the future Lord Justice Coleridge, and its impact upon him was both lasting and profound. Nevertheless, his essentially sacramental approach to nature-which he saw as the repository of types and symbols of the unseen and the spiritual-owed even more to patristic theology; his sense of nature as a sacrament of a divine indwelling may well have derived, too, from Bishop Joseph Butler's influential Analogy of Religion (1736), which established a harmony between natural and revealed religion and natural phenomena. (ODNB)

Tuesday 7 July 2009

The Five Rings and the Nine Commandments

whilst Japanese pull the tools toward them (much more intuitive, i think). In Tora Dojo, our sensei very often emphasises the importance of the returning hand during a punch. Often, we do motion studies just to focus on the returning hand. Anther theme that is constantly stressed is the gathering up of energy from the ground and inwards before release. In Japanese woodworking,

whilst Japanese pull the tools toward them (much more intuitive, i think). In Tora Dojo, our sensei very often emphasises the importance of the returning hand during a punch. Often, we do motion studies just to focus on the returning hand. Anther theme that is constantly stressed is the gathering up of energy from the ground and inwards before release. In Japanese woodworking,  pulling the kanna, or hand plane, is an act that reflects this motion, engaging the woodworker's body in rhythmic movement and stances similar to those in karate. The attention to a centre of gravity and from 'rooting' one's actions in the earth is further paralleled in the position of the woodworker, who typically sits on the ground, sometimes even atop the work piece.

pulling the kanna, or hand plane, is an act that reflects this motion, engaging the woodworker's body in rhythmic movement and stances similar to those in karate. The attention to a centre of gravity and from 'rooting' one's actions in the earth is further paralleled in the position of the woodworker, who typically sits on the ground, sometimes even atop the work piece. The connection between martial arts and woodworking is the underlying metaphor of Miyamoto Musashi's seminal A Book of Five Rings, in which the way of the warrior is compared to the way of the carpenter.

The connection between martial arts and woodworking is the underlying metaphor of Miyamoto Musashi's seminal A Book of Five Rings, in which the way of the warrior is compared to the way of the carpenter. - Do not think dishonestly.

- The Way is in training.

- Become acquainted with every art.

- Know the Ways of all professions.

- Distinguish between gain and loss in worldly matters.

- Develop intuitive judgement and understanding for everything.

- Perceive those things which cannot be seen.

- Pay attention even to trifles.

- Do nothing which is of no use.

Fourthly the Way of the artisan. The Way of the carpenter is to become proficient in the use of his tools, first to lay his plans with a true measure and then perform his work according to plan. Thus he passes through life. These are the four Ways of the gentleman, the farmer, the artisan and the merchant.Comparing the Way of the carpenter to strategy

The comparison with carpentry is through the connection with houses. Houses of the nobility, houses of warriors, the Four houses, ruin of houses, thriving of houses, the style of the house, the tradition of the house, and the name of the house. The carpenter uses a master plan of the building, and the Way of strategy is similar in that there is a plan of campaign. If you want to learn the craft of war, ponder over this book. The teacher is as a needle, the disciple is as thread. You must practice constantly.

Like the foreman carpenter, the commander must know natural rules, and the rules of the country, and the rules of houses. This is the Way of the foreman.

The foreman carpenter must know the architectural theory of towers and temples, and the plans of palaces, and must employ men to raise up houses. The Way of the foreman carpenter is the same as the Way of the commander of a warrior house.

In the contruction of houses, choice of woods is made. Straight un-knotted timber of good appearance is used for the revealed pillars, straight timber with small defects is used for the innter pillars. Timber of the finest appearance, even if a little weak, is used for the thresholds, lintels, doors, and sliding doors, and so on. Good strong timber, though it be gnarled and knotted, can always be used discreetly in construction. Timber which is weak or knotted throughout should be used as scaffolding, and later for firewood. The foreman carpenter allots his men work according to their ability. Floor layers, makers of sliding doors, thresholds and lintels, ceilings and so on. Those of poor ability lay the floor joist, and those of lesser ability carve wedges and do such miscellaneous work. If the foreman knows and deploys his men well the finished work will be good.

The foreman should take into account the abilities and limitations of his men, circulating among them and asking nothing unreasonable. He should know their morale and spirit, and encourage them when necessary. This is the same as the principle of strategy.

The Way of Strategy

Like a trooper, the carpenter sharpens his own tools. He carries his equipment in his tool box, and works under the direction of his foreman. He makes culumns and girders with an axe, shapes floorboards and shelves with a plane, cuts fine openwork and carvings accurately, giving as excellent a finish as his skill will allow. This is the craft of carpenters. When the carpenter becomes skilled and understands measures he can become a foreman.

The carpenter's attainment is, having tools which will cut well, to make small shrines, writing shelves, tables, paper lanterns, chopping boards and pot-lids. These are the specialities of the carpenter. Things are similar for the trooper. You ought to think deeply about this.

The attainment of the carpenter is that his work is not warped, that the joints are not misaligned, and that the work is truly planed so that it meets well and is not merely finished in sections. This is essential.

If you want to learn this Way, deeply consider the things written in this book one at a time. You must do sufficient research.