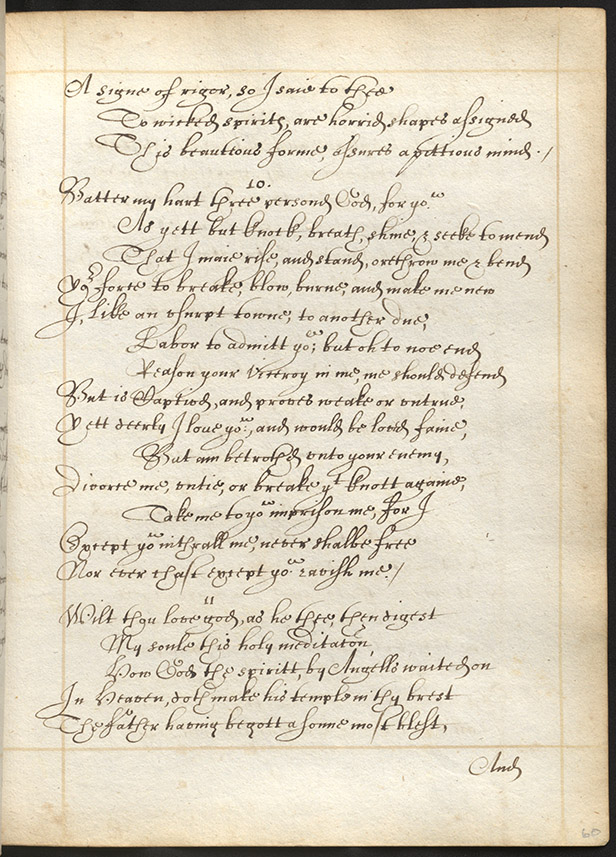

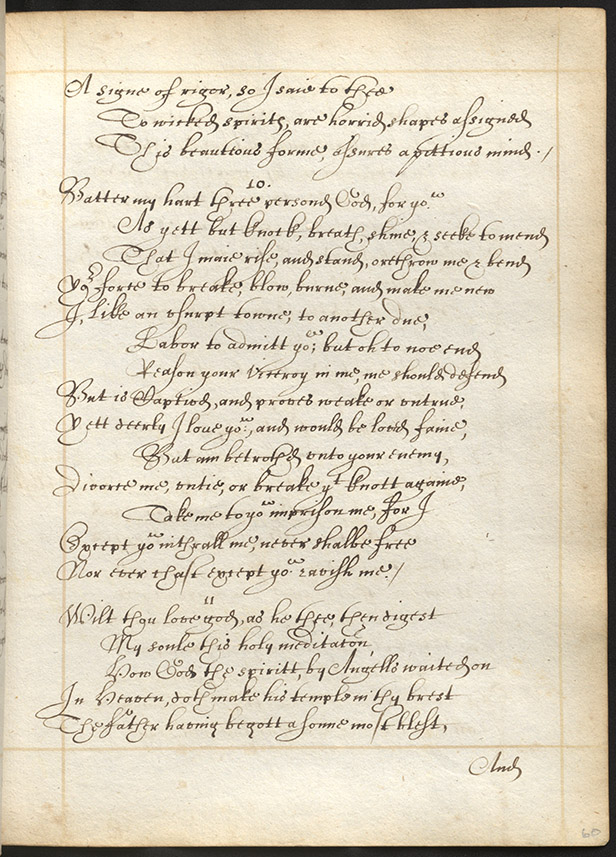

This image was taken from Digital Donne--a great online source for digital images of Donne's manuscripts and early editions

This image was taken from Digital Donne--a great online source for digital images of Donne's manuscripts and early editionsAh, John Donne. Today, 31 March, is

set aside for him by the Church of England. However, due to holiday schedules colliding, i think St. Joseph knocked Donne off the calendar this year. Personally, i think the guy should get a month, forget a day. Sometimes i think this blog takes the form of the Anglican calendar, oddly. For an article on another Jewish girl who likes Donne, click

here. For a short bio from Wikipedia, click

here. To see Donne's recent makeover, click

here.

What can one possibly say about Donne that hasn't already been said? Well, i'll have a crack at it. Firstly, the guy was totally ADD. If he wasn't, his expression of the natural difficulty with which many of us struggle whilst at prayer makes me like him even more:

I throw myself down in my Chamber, and I call in, and invite God, and his Angels thither, and when they are there, I neglect God and his Angels, for the noise of a fly, for the rattling of a coach, for the whining of a door. . .A memory of yesterday’s pleasures, a fear of tomorrows dangers, a straw under my knee, a noise in mine ear, a light in mine eye, an anything, a nothing, a fancy, a Chimera in my brain, troubles me in my prayer. So certainly is there nothing, nothing in spiritual things, perfect in this world.

I think that's what most people like about Donne; he was so human, so accessible. Milton seems to constantly boom down at you from on high, but Donne seems to be struggling with all the other mortals.

Donne has this way of perceiving the world which seems to transcend the human perspective. Here is a section of a letter he wrote to Lady Kingsmel upon the death of her husband on the 26 October 1624:

Nothing disproportions us, nor makes us so incapable of being reunited to those whom we loved here, as murmuring, or not advancing the goodness of Him, who hath removed them from hence. We would wonder, to see a man, who in a wood were left to his liberty, to fell what trees he would, take onely the crooked, and leave the streightest trees; but that man hath perchance a ship to build, and not a house, and so hath use of that kinde of timber: let not us, who know that in Gods house there are many Mansions, but yet have no modell, no designe of the forme of that building, wonder at His taking in of his materials, why he takes the young, and leaves the old, or why the sickly overlive those, that had better health.

True, it doesn't always do the trick, but when you are struggling with the idea of death or dealing with the death of family or friends, this analogy gives you pause. We tend to blame God; Donne asserts that this distances us from the dead. The metaphor he uses for a craftsman who needs different woods for different purposes is great, too.

Here's another section of God as a craftsman. It reminds me of the poem כי הנה כחומר, in the Jewish liturgy of the High Holy Days. To hear the prayer in about 9 different versions, click

here.

When Man was fallen, God clothed him, made him a leather garment; there god descended to one occupation. When the time of Man's redemption was come, then God, as it were, to house him, became a carpenter's son; there God descended to another occupation. Naturally, without doubt, Man would have been his own tailor and his own carpenter; something in these kinds Man would have done of himself, though he had no pattern from God. But . . . in preserving Man from perishing in the Flood, God descended to a third occupation, to be his shipwright, to give him the model of a ship, an Ark, and so to be the author of that, which man himself in likelihood would never have thought of, a means to pass from nation to nation.

from A Sermon . . . Preached to the Honorable Company of the Virginia Plantation, 13 November 1622

Finally, in the vein of Rosh Hashana, or the High Holy Days, i'll close with a great piece by Donne on the nature of sin, called 'A Hymn to God the Father':

WILT Thou forgive that sin where I begun,

Which was my sin, though it were done before?

Wilt Thou forgive that sin, through which I run,

And do run still, though still I do deplore?

When Thou hast done, Thou hast not done,

For I have more.

Wilt Thou forgive that sin which I have won

Others to sin, and made my sin their door?

Wilt Thou forgive that sin which I did shun

A year or two, but wallowed in a score?

When Thou hast done, Thou hast not done,

For I have more.

I have a sin of fear, that when I have spun

My last thread, I shall perish on the shore ;

But swear by Thyself, that at my death Thy Son

Shall shine as he shines now, and heretofore ;

And having done that, Thou hast done ;

I fear no more.